Design’s subplots and the time that goes missing

My first academic paper in design was accepted at the IADRS 2025 conference this December. It was the outcome of two years of commissioned work and trust-building in Xinlong Village in Northern Guangdong—along with many late nights struggling in front of the computer as a novice design-researcher, and the patient, steady supervision of both of my PhD advisors.

The paper, finally titled Foregrounding subplots and shifting practices in co-design: an ethnographic journey in a Chinese village (expected to be made public in March, 2026), begins with a question that quietly reorganized my entire practice:

How might co-design attune to locally emergent forms of change in rural communities under centralized governance?

Or more simply: How might my practice attune to community?

Looking back from some imagined future, I think this paper will feel pivotal in a personal way. Not because it is extremely very well written (I carry many regrets), but because it marks my first departure from trying to demonstrate “competence” in the tools and processes of my practice. Instead, it marks the beginning of me noticing what was happening in the community _when I was not performing my formal role, which arguably shaped my work far more than any workshop methodologies ever could. These observations provoked difficult questions about what it means for a designer trained in Western traditions to work in a rural Chinese setting.

This departure was prompted by a long-standing unease I had been accumulating toward co-design itself, captured in the slide below.

While co-design has been entrusted with democratizing decision-making and empowering communities, my lived experience told a different story. The disciplinary expectations we place on ourselves often emphasize rational problem-solving and the transfer of expertise, approaches that rarely align with the messiness of everyday life or the rhythms of local culture. Moreover, designers are often invited into communities with the hope that we will help enact national agendas, even when our instincts pull us toward under-recognized or unpopular needs.

I still do not have a systematic answer to “how we might design our way out.” But I realized I could at least stop telling the story of design-involved change-making using the familiar script.

You know the script: the design team sees a problem → applies tools and processes → triggers a series of interventions → and then some observable change follows.

My first instinct to break this script was simply to leave my formal role—to hang out in the village without performing “design.” It was what I later called “leaving through a back door.”

As a research orientation toward the knowledge embodied in informal and everyday experiences, I was informed by practice theories of situated learning (Lave & Wenger, 1991), reflexive practice (Argyris & Schon, 1974), and the idea of the “site of the social” (Schatzki, 2001). More specifically, I adopted design ethnography as the research method, where the designer-researcher’s situated, interventional, collaborative, and reflexive role became the primary lens of understanding.

The research followed a two-year progression of co-design events for age-friendly private and public spaces in Xinlong Village, as the village moved toward becoming a nationally certified Age-Friendly Community (AFC). At least 30 local households and about 20 volunteers directly participated in this effort.

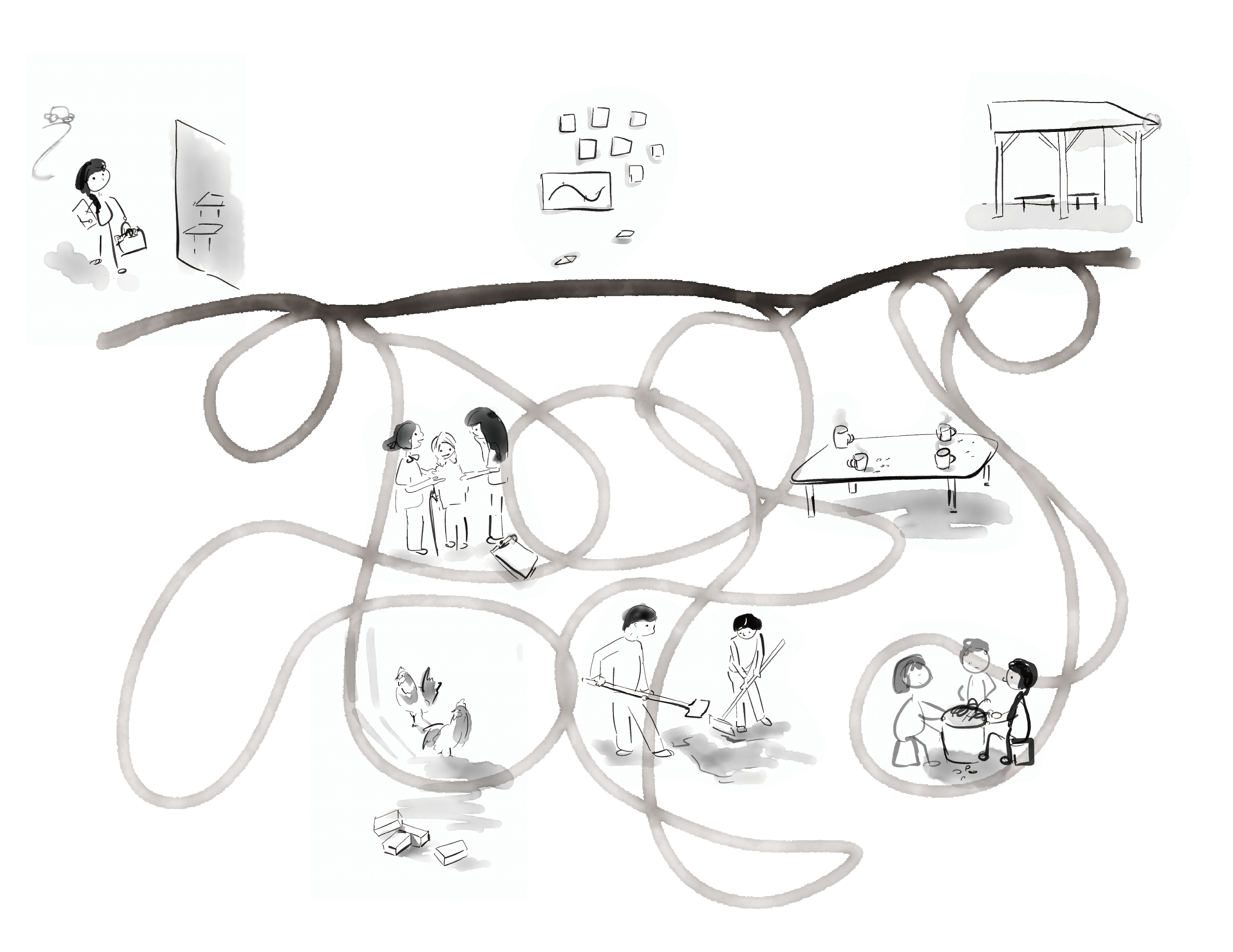

The core of the research was presented through five ethnographic stories.

The first story, “The Abandoned Co-design Prompt,” was about the moment when the communication tool our team designed proved useless in reality—and how five local women spontaneously stepped in, initiating the kinds of natural conversations we were trying so hard to choreograph.

The second story, “So I Just Took Some Bricks” was about discovering that the local leader we assigned to monitor compliance during construction had made numerous changes to our “finalized” design because he saw a better fit with the actual circumstances on the ground.

The third story, “What Is in a Project Title?” followed a conversation with the village secretary, who confided that the community already had the skills needed to create change but lacked the means to raise funds. Her honesty prompted me to question the necessity of my own presence.

The fourth story, “The Secret Village Meeting,” recounted my discovery of an unspoken meeting in the village committee. This meeting resulted in the strategic planting of ideas during our co-design workshop, leading us to falsely believe a particular idea was a triumph of the workshop process.

The final story, “The Peanut Cracking Party,” was based on my experience joining a group of local women who, while cracking peanuts together, collaboratively envisioned a hobby farm and planned it through everyday conversation and shared work.

These stories were not only new insights into community life in Xinlong Village—they also reshaped my design practice in three key ways:

Decentering tools and processes to recenter social relationships

Noticing and nurturing between-project and behind-project spaces

Discovering and joining sites of local creative assemblages

I believe these shifts will continue to reshape my practice in profound ways far into the future.

When one of my supervisors, Dr. Lisa Grocott, read an earlier draft of this paper, she recommended that I look up Sara Ahmed’s concepts of “backgrounding and foregrounding.” This led to one of my favorite sections in the final paper:

“Feminist scholar Sara Ahmed (2012) offers the concepts of foregrounding and backgrounding to describe how certain experiences, bodies, and knowledge are rendered visible or invisible depending on institutional norms. Power, she argues, often operates through what is allowed to appear and what is systematically concealed (ibid.). Drawing on this, I argue that attending to previously backgrounded or unnoticed community dynamics enables designers to surface their own biases and exclusions—and to begin realigning with the perspectives of those historically marginalized in dominant design discourse. In narrative, the subplot reveals what lies beneath the main plot—hidden motivations, quiet conflicts, or unspoken wisdom that shape the story’s unfolding. I position this study as an attempt to foreground the subplots of co-design: to recognize and engage with the less visible, yet deeply influential, rhythms of community life.”

Now, looking at this paper I finished six months ago, and having gone through my first conference experience, I see many things I could have done better. But I’m grateful it carried me this far.

Returning to the research question: How might co-design attune to locally emergent forms of change in rural communities under centralized governance?

I now realized I have not answered it yet with this paper. But perhaps I started somewhere I can build from.

On my way home, I read the distinction between “time of action” and “time in action” posed by economic sociologist Marcin Serafin. “Time of action,” he argues, is the time imposed by external demands, such as a deadline for a funding proposal. “Time in action” is the time we experience when we notice, think, and act, I imagining like the mental gymnastics we go through while writing that same proposal. He writes:

“Whereas time of action can be understood as ‘objective’ time, the time of events happening and structuring social life, time in action is ‘subjective,’ or cognitive; it takes place in the minds of actors. Actors not only experience time in a certain way... but also direct their actions toward a certain moment in time: past, present, or future.” (Serafin, 2016, p. 20)

And I realized that by noticing what had been hidden in conventional design narratives, I too began experiencing the unfolding of design’s contribution to change through an entirely different sense of time. I now see that much design research narrates change as if the designer’s intermittent presence were the full story, falsely stitching together gaps in time.

I am now genuinely curious: what are the missing time intervals in design’s history? (Maybe this is what ethnography is for!)

Imagine pulling the top string by its two ends.

Ahmed, S. (2012). On being included: Racism and diversity in institutional life. Duke University Press.

Argyris, C., & Schön, D. A. (1974). Theory in practice: Increasing professional effectiveness (1st ed.,). Jossey-Bass Publishers.

Schatzki, T. R. (2001). Introduction: Practice Theory. In T. R. Schatzki, K. Knorr Cetina, & E. Von Savigny (Eds.), The Practice Turn in Contemporary Theory. Routledge. [https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203977453](https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203977453)

Serafin, M. (2015). The Temporal Structures of the Economy: The Working Day of Taxi Drivers in Warsaw. 2603474. [https://doi.org/10.17617/2.2218692](https://doi.org/10.17617/2.2218692)